Habitat Programs conserve rare and declining wildlife through restoration and management of grassland, shrubland, and young forest habitats.

MassWildlife’s Habitat Programs works to conserve a variety of wildlife and plants including rare and declining wildlife species identified in the State Wildlife Action Plan, as well as game animals and more common species. In many cases, this happens through restoration and management of grassland, shrubland, and young forest habitats on public and private lands across Massachusetts.

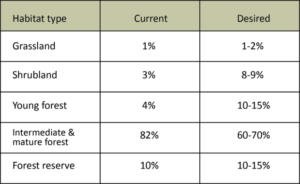

Using information from scientific literature, from biological monitoring, and from private conservation organizations, their Biologists and Foresters set statewide habitat goals for MassWildlife lands. These habitat goals were set to provide high quality habitat for both game and non-game species, and include the establishment of forest reserves.

Many types of wildlife rely on grassland, shrubland, and young forest habitats – all of which are declining in Massachusetts. MassWildlife’s Habitat Programs work to expand these habitat types on state wildlife lands. These lands include Wildlife Management Areas, Wildlife Conservation Easements, and Wildlife Sanctuaries.

MassWildlife management goals for grassland, shrubland, and young forest habitats.

Why is habitat management needed?

Human infrastructure and development have substantially restricted certain natural disturbance processes that historically provided diverse open habitats for wildlife. In particular, flooding and fire are greatly constrained across the landscape today. While control of flooding and fire is essential to protect human life and property, it also creates an obligation on MassWildlife’s part to provide the dynamic habitats for wildlife that these natural processes formerly did. Habitat management is sometimes needed to create, restore, and maintain a variety of habitat types including grasslands.

History of the Massachusetts landscape

Open habitats (grasslands, shrublands and young forest) were part of the New England landscape for centuries prior to European colonization due to:

1. ubiquitous beaver activity

2. spring flooding and ice scouring along rivers and major streams

3. wildfires and fires set by Native Americans in coastal areas and major river valleys

4. occasional catastrophic windstorms

These open habitats started to decline after European colonization due to:

1. extirpation of beaver from Massachusetts

2. extensive development of roads and buildings in portions of the landscape that formerly supported abundant beaver activity

3. flood control

4. fire suppression (especially in portions of the landscape that supported fire-associated natural communities like pitch pine/scrub oak).

Human activity has also reduced the impact of wind storms across the landscape. Today’s forests are relatively young (75 to 90 year old) compared to the old growth that once existed, which means that trees are more pliant and resistant to wind disturbance than original old growth forests. Forests are also fragmented by development in many portions of the landscape, which means that when wind disturbance does occur on forested lands, it is typically interrupted by adjacent development.

MassWildlife uses active management to provide a range of grassland, shrubland, and young forest habitats that are no longer created frequently enough by natural processes. Forestry practices, along with mowing, prescribed burning, and invasive plant control are often used to manage sites.

Wildlife in decline

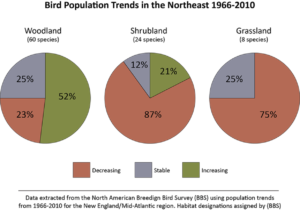

Many kinds of birds, mammals, reptiles, insects, and plants thrive in or near open habitat types. The continuing decline of open grasslands, shrublands, and young forests has impacted a number of wildlife and plant species.

Native grassland and shrubland birds are declining at an alarming rate. Even some forest nesting birds are declining, despite the fact that Massachusetts has more forestland now (nearly 3 million acres) than at any time in the past 300 years. This is because some forest birds (e.g., chestnut-sided warbler) are specialized to nest in young forest, and because other forest birds (e.g., wood thrush) nest in mature forest but then move their young into shrubland and young forest habitats after fledging to utilize abundant food and cover found in these areas.

Reports from the yearly North American Breeding Bird Survey, Massachusetts Audubon Society’s 2013 State of the Birds report, and other published scientific articles, show that species including Eastern Towhee, Field Sparrow, and the Brown Thrasher are all showing alarming declines. Populations of Upland Sandpiper, Vesper Sparrow, and Grasshopper Sparrow (all classified as either Threatened or Endangered in Massachusetts) are also declining. It is clear that without the maintenance and creation of open habitat, birds that require this type of habitat will continue to decline.

Other animals and plants that rely on open habitats are in decline. The New England Cottontail, Massachusetts’ only native cottontail (not to be confused with the Eastern Cottontail, which was introduced to the state in the early 1900s), was once common throughout all of the New England states; now it occurs only sporadically. The Regal Fritillary Butterfly, once common, no longer occurs in the state. Black Racer Snakes and Eastern Box Turtle rely on open habitats for various stages of their life cycle. In addition, many field and grassland plants including New England Blazing Star (a state Special Concern Species), Sandplain Gerardia (a state Endangered Species), and Eastern Silvery Aster (a state Endangered Species) are becoming increasingly rare.

MassWildlife uses active management to provide a range of grassland, shrubland, and forested habitats that are no longer provided frequently enough by natural disturbance processes to help support both common and declining species. Forestry practices, along with mowing, prescribed burning, and invasive plant control are used to manage sites.

Here in the Berkshires, MassWildlife has implemented successful management plans in several areas such as the Stafford Hill Wildlife Management Area in Cheshire and the Moran WMA in Windsor to name a couple. I believe a prescribed burn was scheduled sometime this year in Sheffield.

If you are of my generation, you may remember many of our local farms going out of business and their grasslands becoming overgrown with shrubs, wild blackberries, black caps, raspberries, blueberries, grapes and other vegetation that the birds and critters liked to eat. The abandoned orchards were especially good places for deer, rabbit and partridge hunting. MassWildlife does not have to work hard to convince us of the value of its habitat programs. We grew up in those places and saw the wildlife first hand……before the housing developments.

Go to the Massachusetts State Wildlife Action Plan for more information.

The Quabbin Controlled Deer Hunt

The Quabbin Controlled Deer Hunt is an annual event conducted on Quabbin Reservoir watershed lands, implemented as part of the management program to maintain a balance between deer herd densities and forest regeneration. Participants are selected from an applicant pool in a special lottery in early September. The application must be filled out on line and submitted from the DCR Deer Hunt web page between July 1 and August 31. Hunters can get assistance completing the online application at the Quabbin Visitor Center on Saturdays (9 a.m. to noon) and Wednesdays (noon to 3 p.m.) during the application period.

Following input from the public, Quabbin Park has been added to the White-tailed Deer Management Program at Quabbin in 2019. The application is available from August 1 to August 31.

Once selected, all successful applicants will receive written notification by early to mid-October. If you have any questions or concerns, contact https://www.mass.gov/service-details/quabbin-reservation-deer-hunt:

Bird Language

Next Tuesday at J Allen’s Clubhouse,41 North Street, Pittsfield, the Pittsfield Green Drinks will be having Kevin Bose as its guest speaker to talk about bird language. Starting at 5:15 PM they will chat and nosh, and at 6 PM Kevin will give a 30-minute talk.

All animals (and once all humans), listen with great awareness to the vocalizations of the birds. When we practice tuning our awareness to bird language, we can learn about so many unseen things happening on the landscape – such as where the fox, weasel, and cooper’s hawk are. Through this practice we can come to a deeper understanding of ecological interconnections, as well as make us better listeners throughout our lives.

Kevin Bose has mentored children and adults of all ages in nature and permaculture for over a decade. In a year-long program that combined these two things (called RDNA) he was mentored by Jon Young (author of What the Robin Knows), in bird language as a core routine for Nature Connection.

So, who/what is Green Drinks? Sponsored by the Berkshire Environmental Action Team (BEAT), it is a group of people who meet the 3rd Tuesday of every month, .and usually have a guest speaker. It is billed as great way of catching up with people you know and for making new contacts. The drinks aren’t green but the conversations are. Everyone is welcome and encouraged to bring your questions! It is free and open to the public.